Proteinuria, the presence of excess protein in the urine, can be classified into two primary types: Glomerular and Tubular Proteinuria. While they might sound similar, they stem from distinct mechanisms within the kidneys and can have varying implications for one’s health. We will delve into the differences between glomerular and tubular proteinuria, their underlying causes, diagnostic methods, and potential treatment approaches.

What is Glomerular Proteinuria?

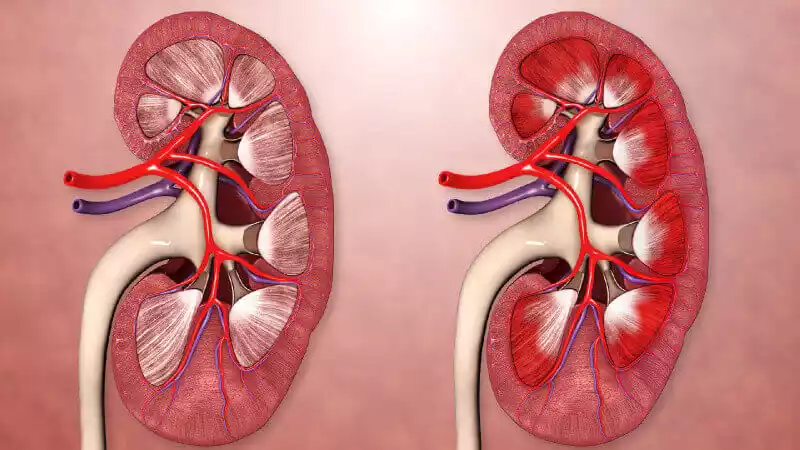

Glomerular proteinuria refers to the excessive leakage of proteins, primarily albumin, and other large molecules, from the bloodstream into the urine due to dysfunction or structural abnormalities of the glomerular filtration barrier in the kidneys. This barrier normally acts as a selective sieve, allowing small molecules to pass into the renal tubules for eventual reabsorption while preventing larger proteins from entering the urine.

In glomerular proteinuria, this selective barrier becomes compromised, leading to the presence of significant amounts of proteins in the urine. It often indicates underlying kidney conditions such as glomerulonephritis, diabetic nephropathy, or systemic lupus erythematosus, and its detection and diagnosis play a crucial role in assessing kidney function and planning appropriate management strategies.

Causes of Glomerular Proteinuria

Glomerular proteinuria can arise from various underlying causes, often related to dysfunction or structural changes within the glomerular filtration barrier. Some common causes include:

-

- Glomerulonephritis: Inflammation of the glomeruli can disrupt the filtration barrier, allowing proteins to leak into the urine. Different types of glomerulonephritis, such as focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) and membranous nephropathy, can lead to glomerular proteinuria.

- Diabetic Nephropathy: Long-term uncontrolled diabetes can damage the small blood vessels in the glomeruli, impairing their function and causing protein leakage.

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE): This autoimmune disorder can result in immune complexes depositing in the glomeruli, triggering inflammation and damage to the filtration barrier.

- Amyloidosis: Deposits of abnormal proteins (amyloids) in the glomeruli can disrupt their normal function and contribute to proteinuria.

- Preeclampsia: A condition that occurs during pregnancy, characterized by high blood pressure and kidney dysfunction, which can lead to glomerular damage and proteinuria.

- IgA Nephropathy: Also known as Berger’s disease, it involves the buildup of immunoglobulin A (IgA) in the glomeruli, leading to inflammation and protein leakage.

- Alport Syndrome: A genetic disorder affecting the structure of collagen in the glomerular basement membrane, causing progressive kidney damage and proteinuria.

- Hypertensive Nephropathy: Chronic high blood pressure can damage the blood vessels in the glomeruli, impairing their function and causing proteinuria.

- Minimal Change Disease: A kidney disorder primarily affecting children, characterized by minimal changes visible under a microscope but leading to significant proteinuria.

- Hereditary Nephritis: Genetic conditions like thin basement membrane nephropathy can result in structural abnormalities in the glomeruli, leading to proteinuria.

- Infections: Some infections, such as poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis, can cause inflammation and damage to the glomeruli, resulting in proteinuria.

These are just a few examples of the many potential causes of glomerular proteinuria. Identifying the specific underlying cause is crucial for determining appropriate treatment and management strategies.

What is Tubular Proteinuria?

Tubular proteinuria refers to the presence of an abnormal amount of proteins, particularly smaller proteins, in the urine due to impaired reabsorption or direct damage to the renal tubules within the kidneys. In normal kidney function, most of the proteins that are filtered through the glomerulus are reabsorbed by the renal tubules and returned to the bloodstream.

When the tubular reabsorption process is compromised, proteins that would normally be reabsorbed end up being excreted in the urine. This type of proteinuria often suggests dysfunction or injury to the renal tubules and can be associated with conditions such as tubulointerstitial nephritis, Fanconi syndrome, and other disorders affecting the tubular function.

Causes of Tubular Proteinuria

Tubular proteinuria can occur due to various factors that disrupt the normal processes of protein reabsorption within the renal tubules. Some common causes include:

-

- Tubulointerstitial Nephritis: Inflammation of the tubules and the interstitial tissue can impair their function, leading to reduced reabsorption of proteins. This can be caused by infections, autoimmune diseases, drug reactions, and other inflammatory conditions.

- Fanconi Syndrome: A rare disorder where the proximal renal tubules fail to reabsorb several substances, including proteins, electrolytes, and glucose. It can be acquired (due to medications or toxins) or inherited.

- Multiple Myeloma: This cancer of plasma cells can result in the overproduction of light chains, which can overwhelm the tubular reabsorption capacity, leading to their excretion in the urine.

- Sjögren’s Syndrome: An autoimmune disorder that can cause inflammation and damage to various tissues, including the renal tubules, resulting in proteinuria.

- Wilson’s Disease: A genetic disorder affecting copper metabolism that can lead to copper deposition in the kidneys and tubular dysfunction.

- Nephropathic Cystinosis: An inherited disorder that leads to the accumulation of the amino acid cystine within cells, including renal tubular cells, causing tubular damage and proteinuria.

- Amyloidosis: As with glomerular proteinuria, the deposition of abnormal proteins (amyloids) in the renal tubules can impair their function and contribute to proteinuria.

- Light Chain Tubulopathy: In some cases of monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance (MGRS), light chains from abnormal immunoglobulins can directly damage the renal tubular cells.

- HIV-Associated Nephropathy: HIV infection can affect the renal tubules, leading to impaired reabsorption of proteins and resulting in proteinuria.

- Certain Medications and Toxins: Some medications and toxins can directly damage the renal tubules, affecting their ability to reabsorb proteins.

- Genetic Tubular Disorders: Various inherited conditions can affect tubular function, leading to proteinuria. Examples include Dent’s disease and Lowe syndrome.

It’s important to identify the underlying cause of tubular proteinuria to guide appropriate treatment and management approaches.

Comparative Table of Glomerular and Tubular Proteinuria

Here’s a comparative table outlining the key differences between glomerular and tubular proteinuria:

| Aspect | Glomerular Proteinuria | Tubular Proteinuria |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Leakage of larger proteins into urine due to glomerular barrier dysfunction | Presence of smaller proteins in urine due to impaired tubular reabsorption or tubular damage |

| Mechanism | Glomerular filtration barrier abnormalities | Impaired tubular reabsorption or tubular damage |

| Types of Proteins | Primarily albumin and larger proteins | Smaller proteins, such as alpha-1 microglobulin, beta-2 microglobulin, and retinol-binding protein |

| Clinical Features | Foamy or frothy urine, generalized edema (in severe cases), hypoalbuminemia | May include generalized weakness, bone pain (in multiple myeloma-related cases), other signs of tubular dysfunction |

| Diagnosis | Elevated urinary protein-to-creatinine ratio, presence of albumin in urine, reduced serum albumin levels | Elevated levels of specific tubular proteins in urine, urine protein electrophoresis |

| Associated Conditions | Glomerulonephritis, diabetic nephropathy, systemic lupus erythematosus | Tubulointerstitial nephritis, Fanconi syndrome, multiple myeloma |

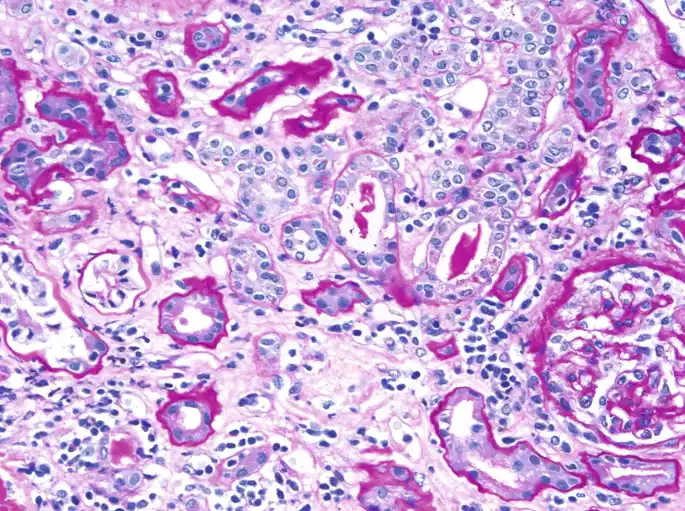

| Microscopic Examination | May show glomerular changes under a microscope | May show tubular cell abnormalities under a microscope |

| Prognosis | Can progress to chronic kidney disease if not managed | Can lead to electrolyte imbalances, tubulointerstitial fibrosis if not managed |

| Treatment | Address underlying cause (e.g., treat glomerulonephritis), manage symptoms | Treat underlying cause (e.g., discontinue offending drugs), manage symptoms and complications |

| Management | Focus on preserving kidney function, controlling proteinuria, blood pressure, and fluid balance | Emphasize correction of electrolyte imbalances, manage complications, and prevent tubular damage |

| Long-Term Outlook | Progression can be slowed with early intervention | Outcomes vary based on the underlying cause and severity |

Remember that this table provides a simplified overview of the main differences between glomerular and tubular proteinuria. In clinical practice, these conditions can have complex presentations and interactions, so a thorough medical assessment is crucial for accurate diagnosis and management.

Similarities between Glomerular and Tubular Proteinuria

Here are some similarities between glomerular and tubular proteinuria:

- Protein Presence: Both involve the presence of proteins in urine due to kidney dysfunction.

- Kidney Damage: Indicate potential damage to different parts of the kidney – glomeruli or tubules.

- Diagnostic Tests: Detected through urinalysis and urine protein-to-creatinine ratio.

- Underlying Causes: Can be linked to autoimmune conditions or systemic disorders.

- Chronic Kidney Disease: If unmanaged, both can contribute to the progression of kidney disease.

- Monitoring: Regular monitoring of kidney function is essential in both cases.

- Treatment Goals: Aim to identify and address underlying causes to prevent complications.

- Renal Replacement: In severe cases, both might necessitate kidney replacement therapy.

- Importance of Early Intervention: Timely diagnosis and management are vital for both conditions.

Diagnosis of Glomerular and Tubular Proteinuria

Diagnosing glomerular and tubular proteinuria involves a series of clinical assessments and laboratory tests to determine the underlying cause and guide appropriate treatment. Here’s an overview of how each type is diagnosed:

Diagnosing Glomerular Proteinuria:

-

- Urinalysis: Microscopic examination of urine to check for the presence of red and white blood cells, casts, and other abnormalities that might suggest glomerular damage.

- Urine Protein-to-Creatinine Ratio: A simple test that measures the amount of protein in the urine relative to the level of creatinine. It provides an estimate of protein excretion and the severity of proteinuria.

- Serum Albumin Levels: Low serum albumin levels might indicate significant protein loss through the urine.

- Kidney Function Tests: Blood tests such as serum creatinine and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) assess overall kidney function.

- Specific Protein Tests: If certain glomerular diseases are suspected, specific protein tests like immunoglobulin levels or complement levels might be performed.

- Kidney Biopsy: In cases of unclear diagnosis or to determine the underlying glomerular pathology, a kidney biopsy might be necessary.

Diagnosing Tubular Proteinuria:

-

- Urinalysis: Microscopic examination of urine to identify tubular cells, casts, and other cellular debris that might indicate tubular damage.

- Urine Protein-to-Creatinine Ratio: Similar to glomerular proteinuria, this test helps quantify protein excretion specifically related to tubular dysfunction.

- Measurement of Tubular Proteins: Quantifying specific tubular proteins such as alpha-1 microglobulin, beta-2 microglobulin, and retinol-binding protein in the urine.

- Electrolyte and Blood Gas Analysis: Assessing electrolyte imbalances and acid-base disturbances associated with tubular dysfunction.

- Renal Imaging: Techniques like ultrasound can provide insights into kidney size, structure, and potential obstructions.

- Renal Function Tests: Blood tests like serum creatinine and eGFR are used to assess overall kidney function.

- Specific Tests for Underlying Conditions: If conditions like Fanconi syndrome are suspected, tests for glucose, amino acids, and other substances in the urine might be conducted.

A comprehensive diagnosis often requires a combination of these tests, along with a thorough medical history, physical examination, and consideration of clinical symptoms. Nephrologists, specialists in kidney disorders, play a crucial role in diagnosing and managing both glomerular and tubular proteinuria.

Clinical Implications

The clinical implications of glomerular and tubular proteinuria are significant, as they can provide crucial insights into kidney health and underlying medical conditions.

Understanding these implications helps guide appropriate diagnosis, management, and treatment strategies:

Glomerular Proteinuria:

-

- Kidney Function Assessment: Glomerular proteinuria often indicates glomerular damage and dysfunction. Monitoring proteinuria levels provides valuable information about the extent of kidney impairment.

- Early Detection of Kidney Disease: Detecting glomerular proteinuria early can serve as an indicator of potential kidney diseases, allowing for timely intervention to prevent or slow the progression of chronic kidney disease.

- Risk of Complications: Persistent glomerular proteinuria can lead to complications such as hypoalbuminemia, edema, and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

- Treatment Target: Treating the underlying cause of glomerular proteinuria, such as managing autoimmune conditions or controlling diabetes, can help preserve kidney function and mitigate associated risks.

- Monitoring Response: Monitoring changes in proteinuria over time helps evaluate the effectiveness of treatment and disease progression.

Tubular Proteinuria:

-

- Tubular Dysfunction Identification: Tubular proteinuria is indicative of tubular damage or dysfunction. It can be an early sign of various kidney disorders and conditions affecting tubular health.

- Electrolyte and Acid-Base Imbalances: Tubular dysfunction can lead to electrolyte imbalances and acid-base disturbances due to impaired reabsorption processes.

- Underlying Causes: Identifying the specific proteins present in the urine can provide insights into the underlying cause of tubular dysfunction, aiding in diagnosis.

- Treatment Approach: Addressing the root cause of tubular proteinuria, such as discontinuing nephrotoxic medications or managing specific disorders, is essential to prevent further tubular damage and related complications.

- Preventing Progression: Early intervention and appropriate management can help prevent the progression of tubular dysfunction and minimize the risk of chronic kidney disease.

Monitoring proteinuria levels, kidney function, and the response to treatment is critical for optimal patient care. Nephrologists, along with a multidisciplinary healthcare team, play a vital role in interpreting clinical implications, making accurate diagnoses, and developing tailored management plans for individuals with glomerular and tubular proteinuria.

Treatment Approaches of Glomerular and Tubular Proteinuria

The treatment approaches for glomerular and tubular proteinuria differ based on the underlying causes and mechanisms involved. Here’s an overview of how each type is managed:

Treatment of Glomerular Proteinuria:

- Underlying Cause: Treating the underlying condition responsible for glomerular proteinuria is crucial. This might involve managing autoimmune diseases (like lupus), controlling diabetes, or addressing infections causing glomerulonephritis.

- Blood Pressure Management: Maintaining optimal blood pressure levels helps protect the glomerular filtration barrier. Medications called angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors) or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) are often used.

- Dietary Modifications: Reducing salt intake and managing fluid balance can alleviate edema and help control blood pressure.

- Immunosuppressive Therapy: In cases of immune-mediated glomerular diseases, immunosuppressive medications might be used to suppress the immune response and reduce inflammation.

- Disease-Specific Treatments: Depending on the specific glomerular disease (such as membranous nephropathy or FSGS), disease-specific treatments might be employed.

- Monitoring: Regular monitoring of kidney function, proteinuria levels, and blood pressure helps evaluate treatment effectiveness and disease progression.

Treatment of Tubular Proteinuria:

- Discontinuing Nephrotoxic Agents: If medication-induced, discontinuing or adjusting the dosage of medications causing tubular damage is a primary step.

- Managing Underlying Conditions: Treating conditions like multiple myeloma or Fanconi syndrome can help alleviate tubular dysfunction.

- Electrolyte and Acid-Base Correction: Addressing electrolyte imbalances and acid-base disturbances through supplementation or dietary modifications.

- Avoiding Dehydration: Ensuring adequate fluid intake can help prevent further tubular damage.

- Managing Fanconi Syndrome: Inherited Fanconi syndrome might require supportive treatments such as phosphate and vitamin D supplements.

- Specific Interventions: In cases of genetic disorders causing tubular dysfunction, genetic counseling and disease-specific interventions might be considered.

- Regular Follow-up: Monitoring kidney function, electrolytes, and proteinuria levels helps track treatment response and prevent complications.

Both types of proteinuria benefit from a multidisciplinary approach involving nephrologists, dietitians, pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals. Individualized treatment plans are designed based on the patient’s underlying condition, overall health, and response to interventions. The ultimate goal is to mitigate proteinuria, preserve kidney function, and manage complications to improve the patient’s quality of life.

Final Thoughts

Understanding the distinctions between glomerular and tubular proteinuria is vital for effective diagnosis and treatment. Whether caused by glomerular dysfunction or tubular reabsorption issues, proteinuria serves as a valuable indicator of kidney health. By adopting a proactive approach to kidney care, individuals can mitigate risks, manage underlying conditions, and enhance their overall quality of life.